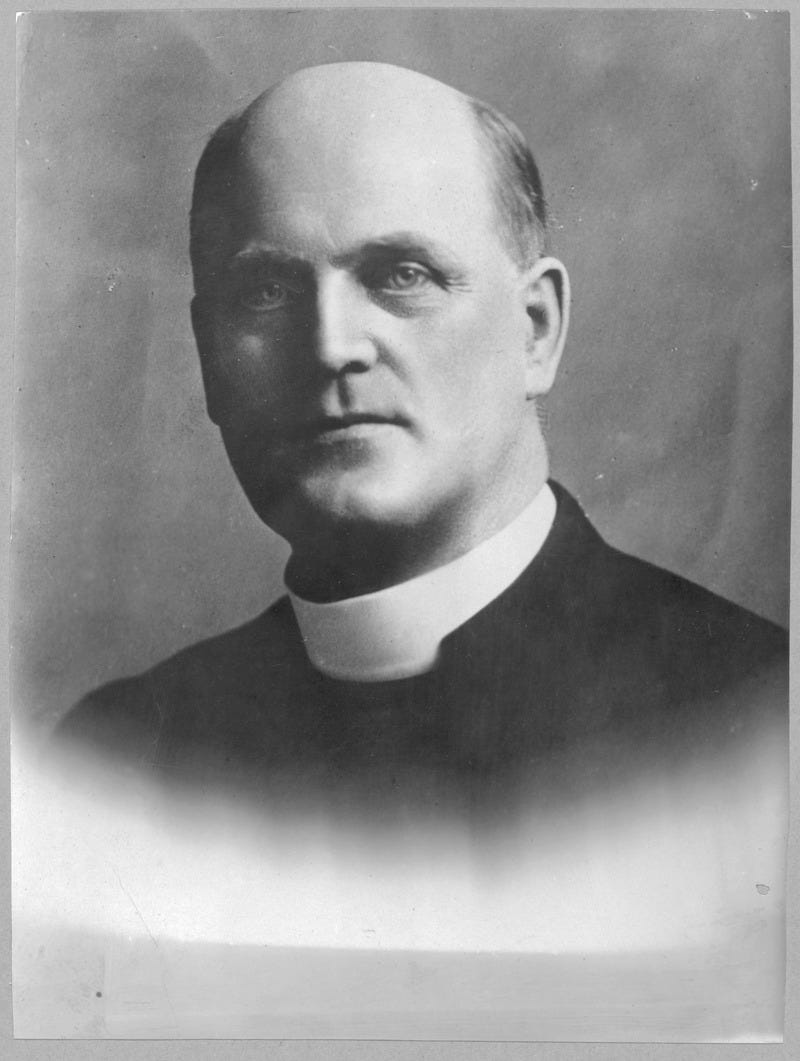

Bishop Isaac Stringer had just finished serving as a substitute bishop for another bishop when he was told he could finally return home. He had spent awhile living in the Northwest Territories, in the Mackenzie River area, when he got the news in September 1909.

The problem was he, and his companion Charles Johnson, couldn’t just fly or drive home. They needed to walk 800 kilometres to return to his diocese and his parishioners.

It was not going to be an easy journey.

As they walked, they soon became lost due to a storm. Their proximity to the magnetic north pole also made their compass useless.

Between them, they had only a little food and two blankets.

By the time it was October, they had been eating only berries and some small game. The winter resulted in no birds or squirrels to hunt and the men were getting desperate.

They decided they would eat the only thing they had left, their boots.

Eating boots was a viable solution to their growing starvation. At the time, boots were made of walrus skin and sealskin. Most importantly, the skin was not tanned.

The men cut the boots into little pieces, then boiled them in water for hours to rehydrate the skin and make it a bit more meaty. After the skin was boiled, they cooked the pieces over the fire.

According to Stringer, the walrus skin was better tasting than the seal skin.

On the day they finished eating their boots, they found sled tracks and freshly-cut trees. They staggered into an Indigenous camp, barely alive. The men there quickly recognized them because they had been reported missing for a month.

Both men had lost 50 pounds in their ordeal and Andrew Cloh, a local man, was able to take them to his home where he fed them fish and rabbit.

Probably the best meal they ever tasted.